Founded by a Persistent Woman

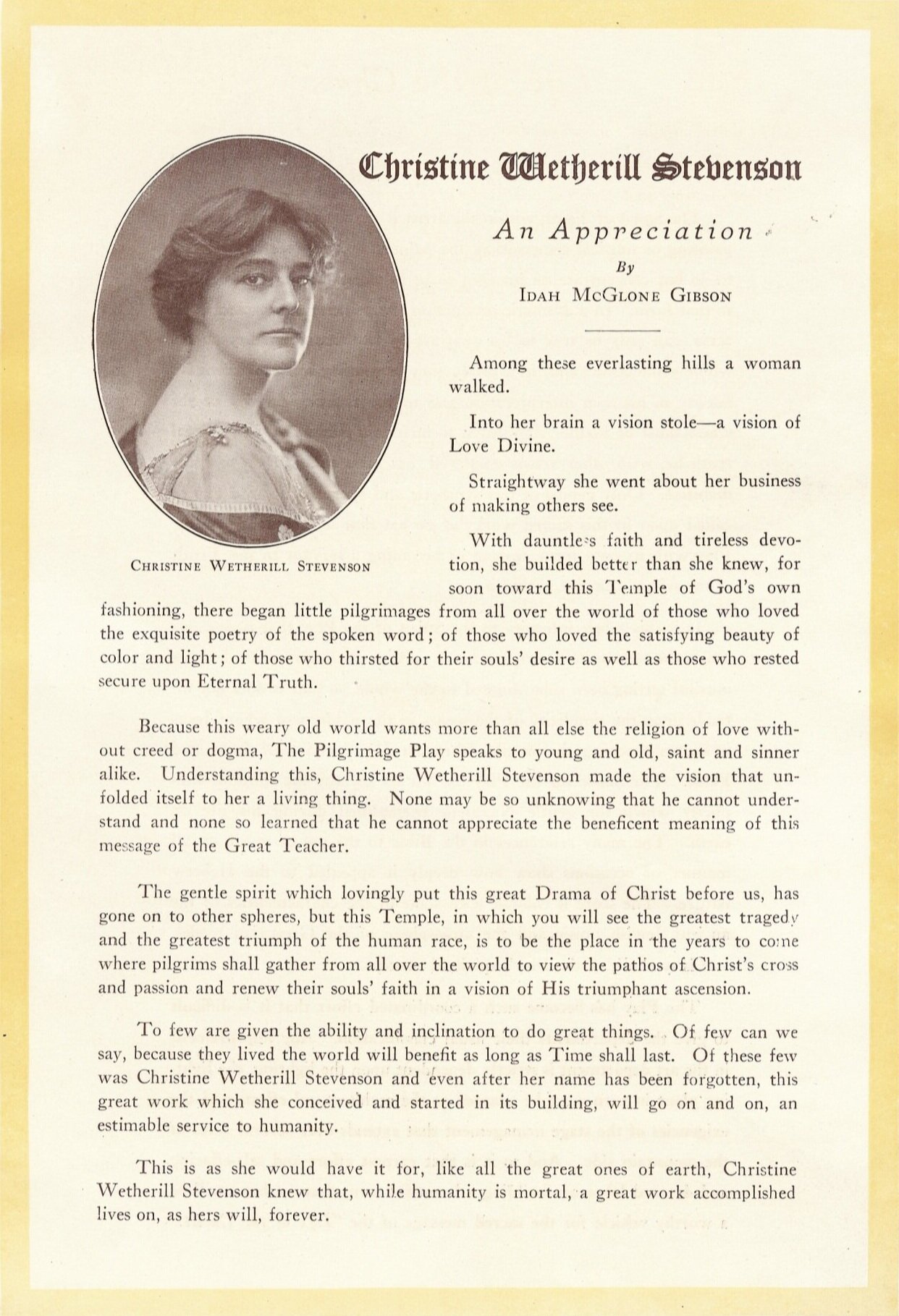

Christine Wetherill Stevenson (1878-1922)

Christine Wetherill Stevenson was born in 1878 in Philadelphia, PA, an heiress of the Pittsburgh Paint Company. A beauty with wealth and charm, she became a social leader, a patron of the arts, and was prominent in the civic life of Philadelphia. Her father gave each of his children $100,000 to use as they desired and Christine decided to spend hers studying music in Paris. After a disastrous production where she lost her voice, she ran off to study painting on a farm on the outskirts of Paris. During this time she met and married York Stevenson, but shortly thereafter she left for India alone to study Buddhism.

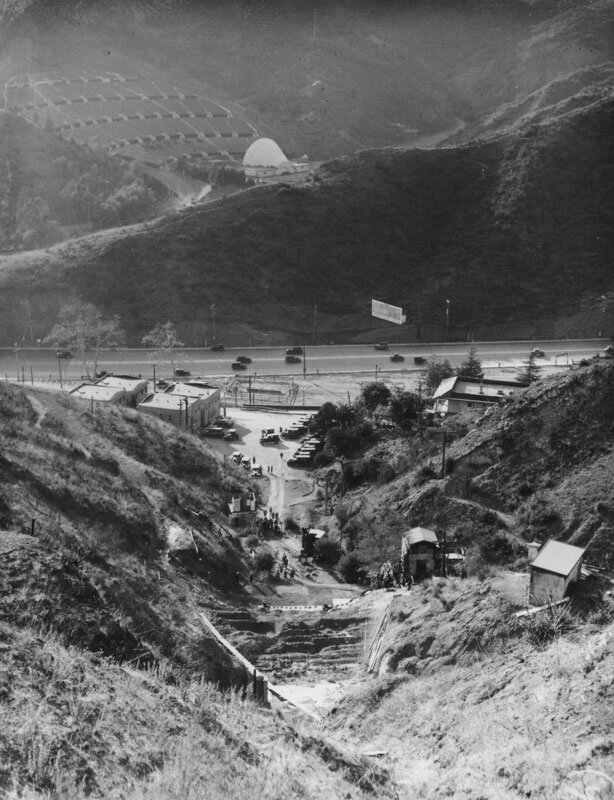

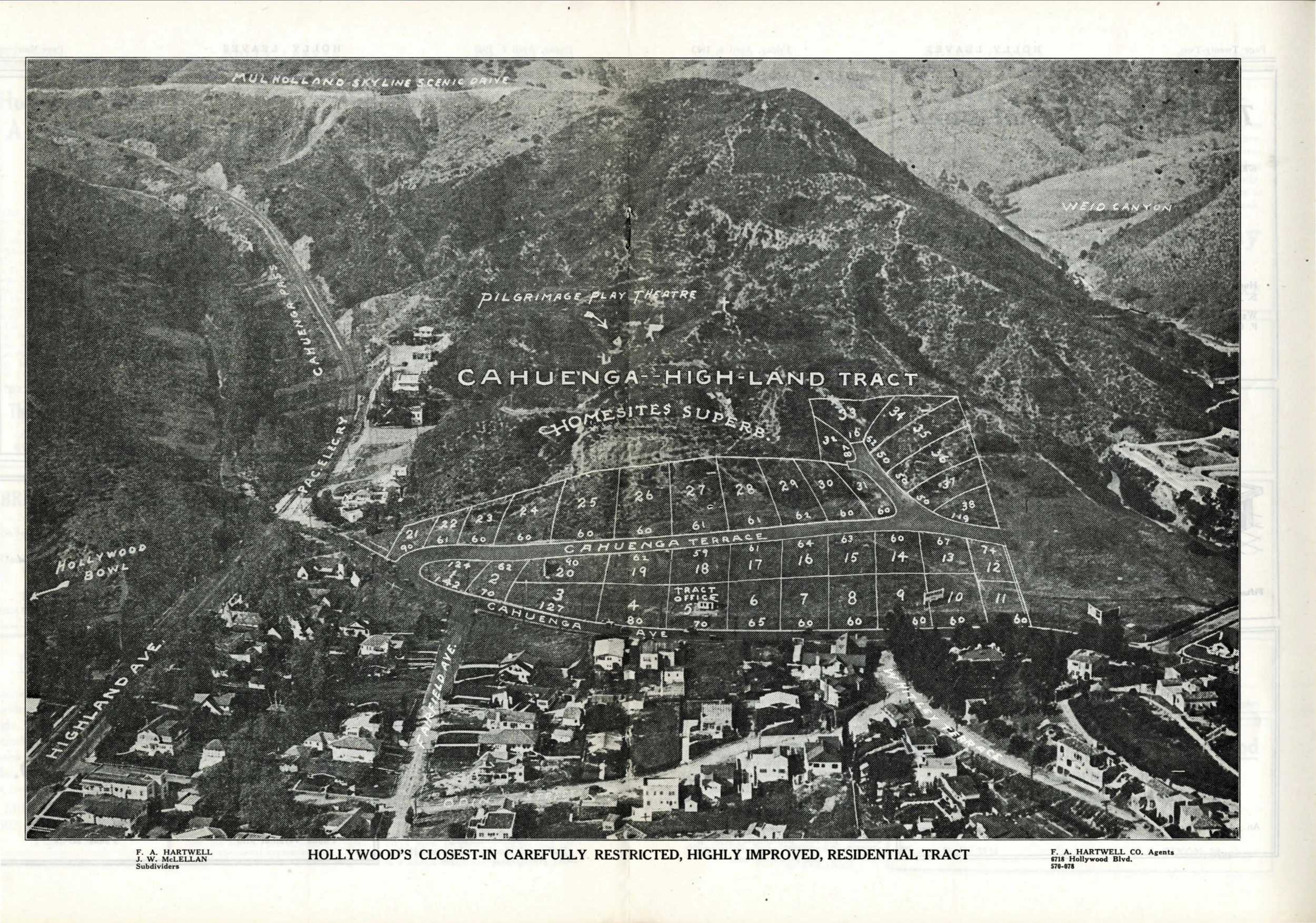

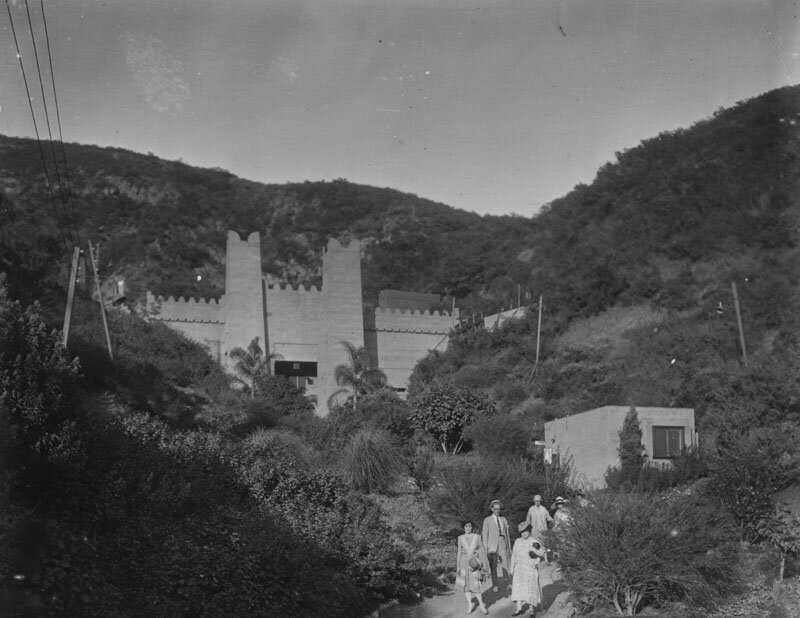

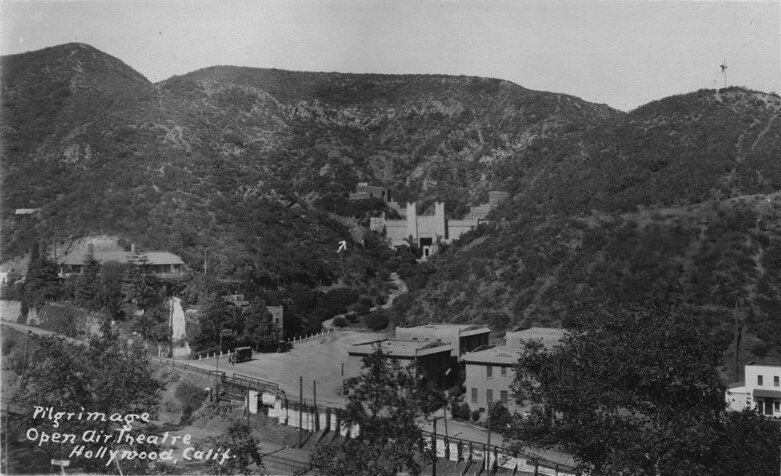

She returned to the US and eventually made her way to Los Angeles and studied theosophy, an esoteric philosophy based on ancient religions and myths, particularly Buddhism, at the Krotona Institute. In 1918, while at Krotona, she produced performances of The Light of Asia, a play about the Buddha, in a canyon in East Hollywood. Soon thereafter, she came across a potential site known as Daisy Dell in the Cahuenga Pass and with the Theatre Arts Alliance, purchased 60 acres of what would become the Hollywood Bowl. After a disagreement with the Alliance about whether religion was appropriate for the stage, Stevenson went off with Harry Ellis Reed to find a new site to stage her Pilgrimage Play. And just across the pass, they found 29 perfect acres for their new venture, which she purchased from the Ivar Weid estate. Weid was notable as a prominent local businessman who originated the name “Hollywood” for the area.

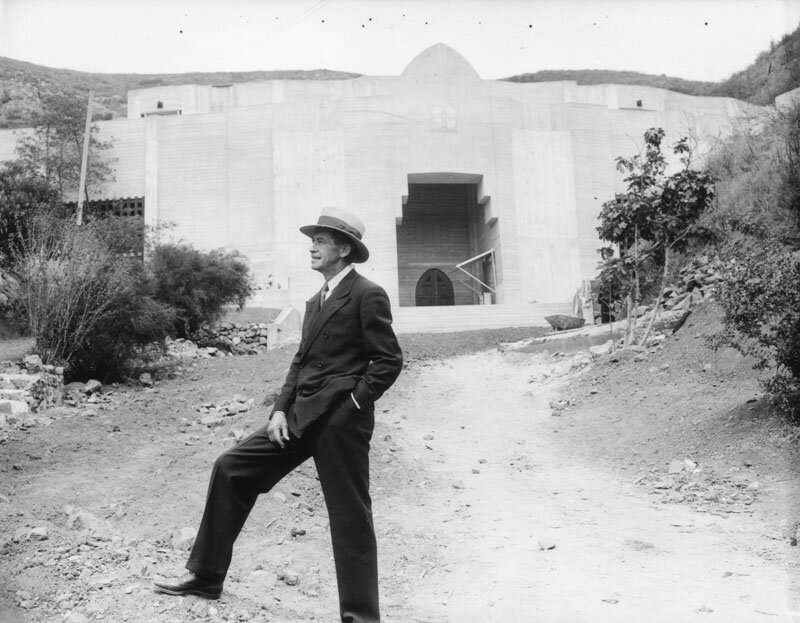

Christine Wetherill Stevenson outside the original Pilgrimage Theatre.

An appreciation of Christine Wetherill Stevenson from the 1924 Pilgrimage Play program.

A 1920 article in Theatre Magazine tells the story best…

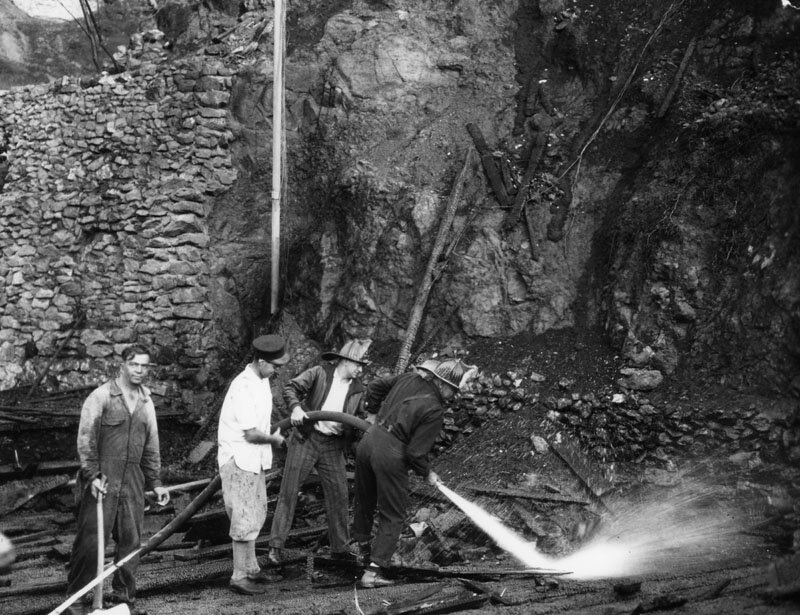

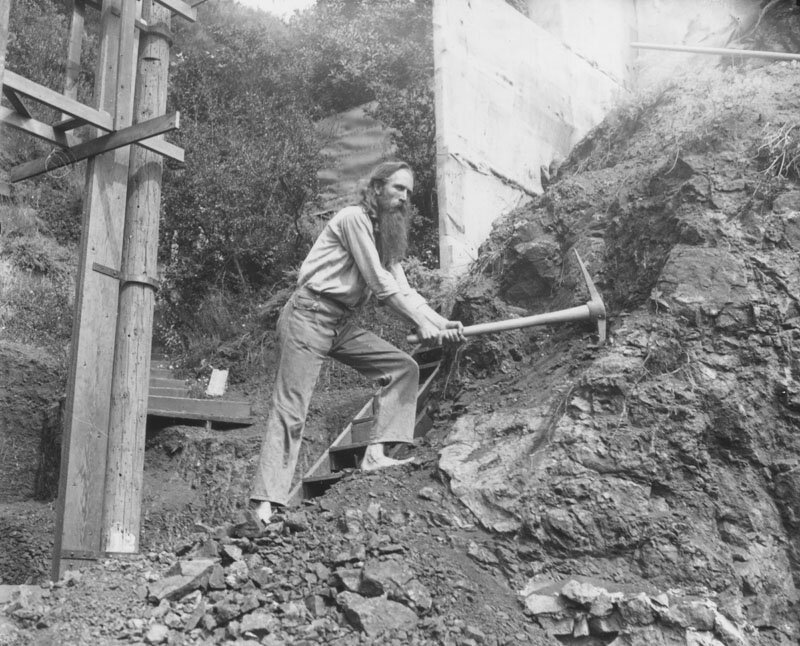

Mrs. Stevenson and Mr. Reed visited the canyon site of the "Pilgrimage Play" early in April this year. They looked over the rugged hillsides and discussed the possibilities of the Scriptural drama. As they argued the various "impossibilities" new vistas opened to them. They discovered a great diamond in the rough. A few days later they took several architects out to look over the ground and submit estimates for the construction of the theatre and stadium. The architects did not think the job could be done in less than six months. The next day found them again on the hillside. Their second impossibility appeared to be the lack of money with which to establish the play.

The interview ended when Mrs. Stevenson declared she was going East to raise money with which to produce the play. "I will telegraph to you when I have enough money to justify a beginning," said she. "Then you can start work."

In three weeks she sent word for Mr. Reed to begin work, and there began a romance of modern achievement which stands perhaps without a parallel. As if by the aid of an almost superhuman agency Reed, the actor, became Reed the engineer. He built eleven stages in the hills, secured and arranged innumerable batteries of stage lights, chose his actors, obtained the costumes, and looked after a multitude of minor details. Five weeks from the day of the beginning, the first performance was given. Only two months' time and $15,000 were spent in making the dream come true.

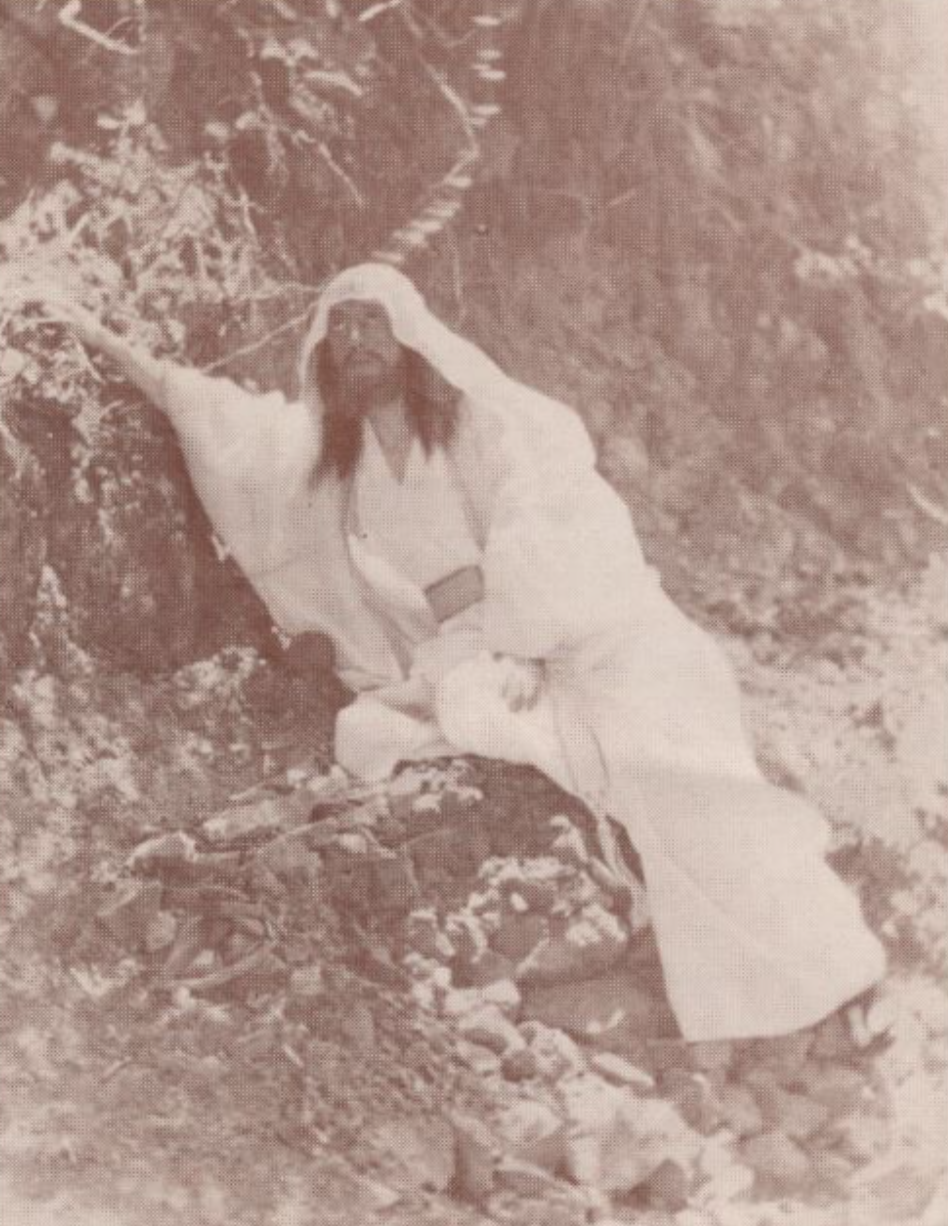

A few queer things happened in that time, of course. Henry Herbert, who took the role of Christ, worked with pick and shovel on the hillsides, along with Judas and most of the twelve apostles. Pay day came and went with no paymaster, but wages did not matter. The true Christ spirit possessed the workers. For the time being the actors and stage hands ceased to be individuals of their particular professions, and became true comrades of the cross. Thus did the "Pilgrimage Play" come into being.

The high hills on either side of the stage have for ages guarded the narrow pass through the mountains to San Francisco, a trail once trodden by the Franciscan Fathers in their weary pilgrimage from mission to mission, for the conversion of the native Californians then mostly Mexicans and Indians to the teachings of Jesus Christ.

Stevenson would have an opportunity to build her theatre and direct her Pilgrimage Play for its first three years. Sadly, she passed away November 21, 1922 at her sister’s home in Media, PA at the age of just 44. She had been on a business trip in New York City for the play and within 10 days of falling ill, reportedly passed on from work exhaustion. At the time, her family had never seen the Pilgrimage Play. So the cast assembled in Philadelphia and the play was given in its entirety for her family to see. On July 12, 1924, in appreciation of her remarkable accomplishment and as a memorial to her, Mr. and Mrs. Wetherill gave the production rights, costumes, and the grounds upon which the play is given, to Los Angeles as a permanent civic asset.

Stevenson wrote the Pilgrimage Play script based on the The Four Gospels according to the King James version of the Bible. The text only uses dialogue from scripture; Stevenson is sometimes referred to as the transcriber of the script, as opposed to the playwright. A 1921 article in the Los Angeles Times noted her return from a research trip to Palestine, Egypt and India, where she bought over $3,000 worth of costumes for the show. The article also noted that olives, figs and grapes would be planted around the theatre to make it appear more like Palestine. Stevenson would go on to produce, write, direct, design costumes for, and act in, the Pilgrimage Play. She planned to produce an entire series of religious dramas featuring religions from around the world, but died before she could realize that dream.

The Holy Land in Hollywood

1920: The Original Pilgrimage Theatre

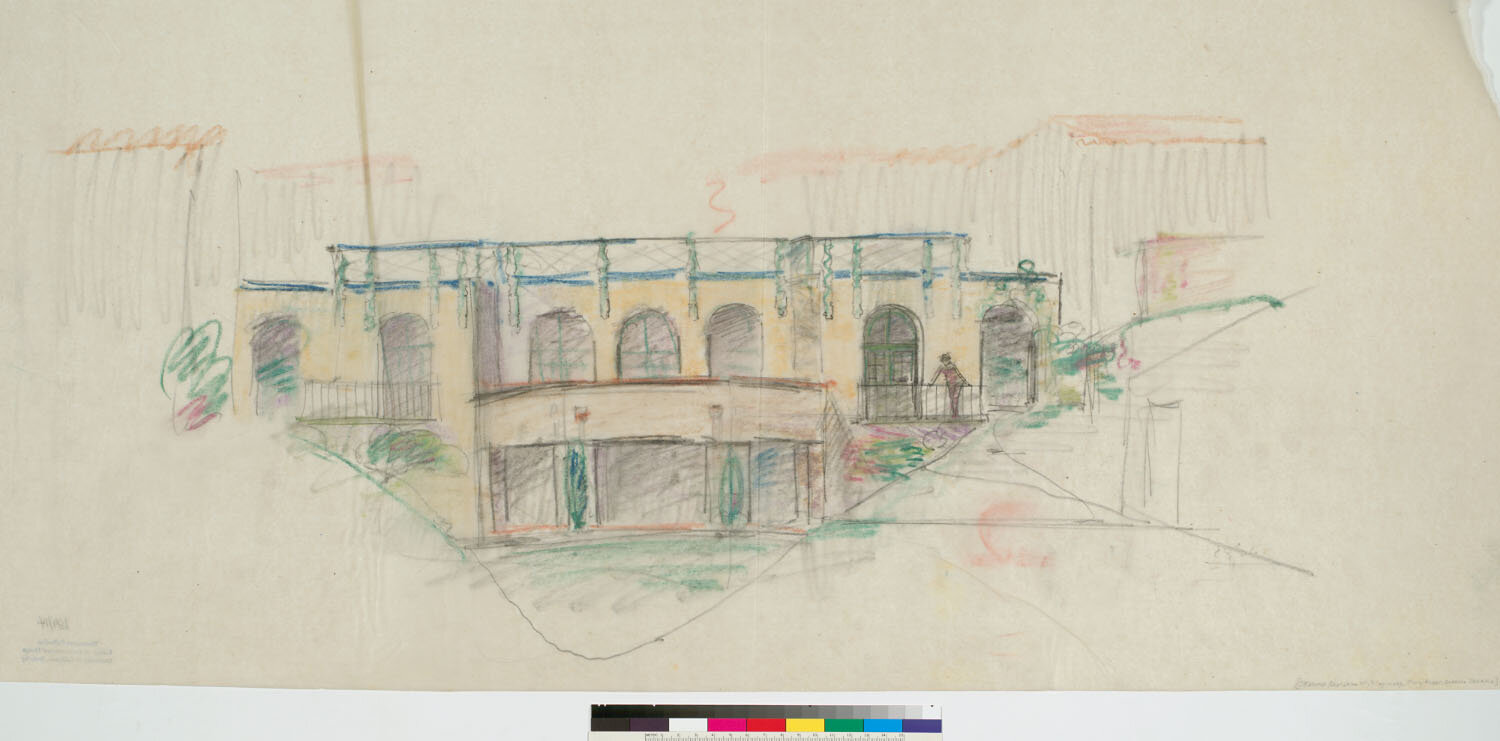

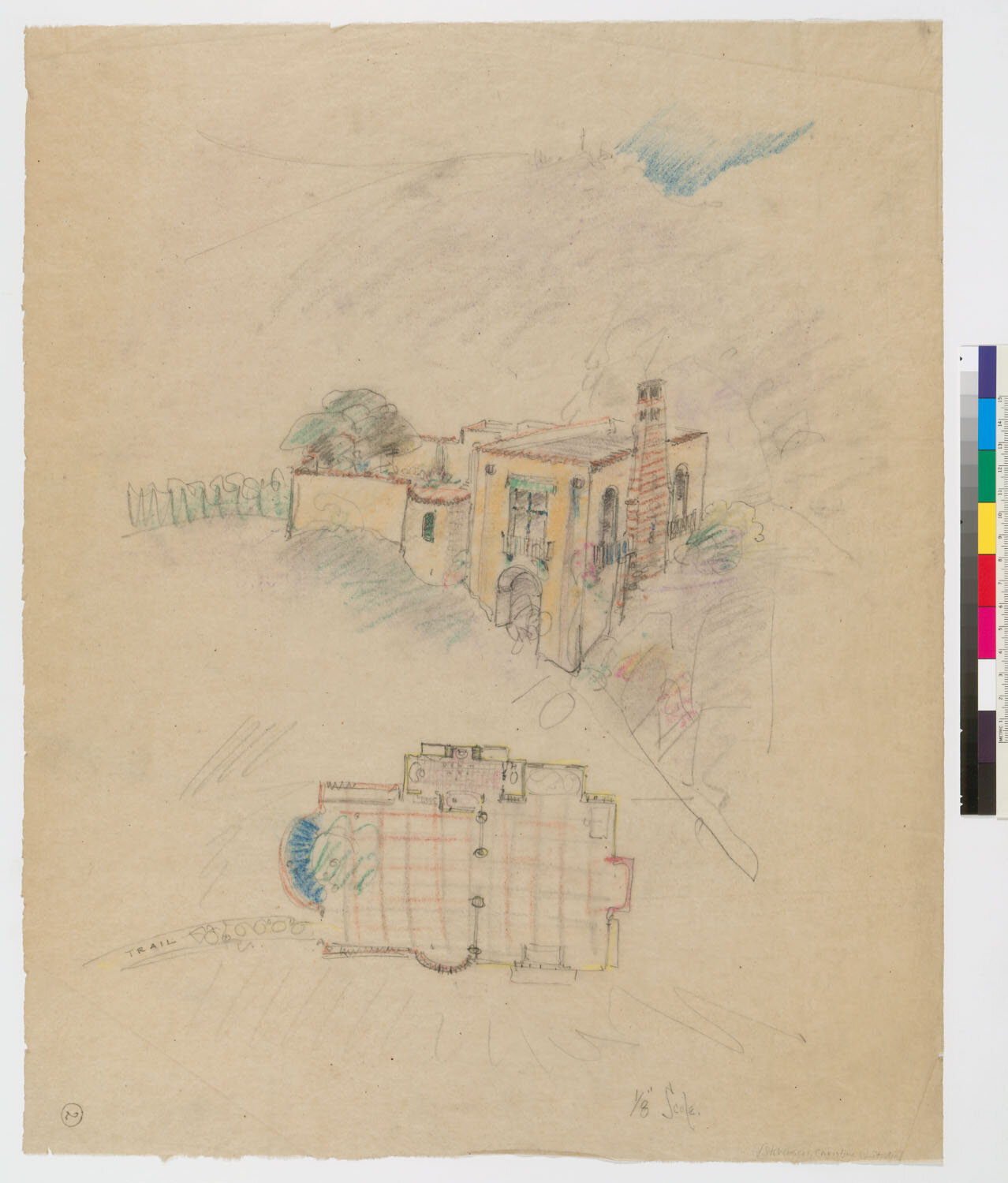

With only a few days notice, the original Pilgrimage Theatre was designed by architect Bernard Maybeck to be a wooden, outdoor amphitheatre. At the time, he was a professor at UC Berkeley and had notable beliefs about how civilization and the land should relate to each other. One of his overriding principles was that the primacy of the landscape should never be subdued by the architecture, an idea he clearly put to use at the Pilgrimage Theatre. In his spare time, he was known to create costumes and design sets for his local Hillside Club in Berkeley, for whom he had also designed a theatre. Below you can see sketches that Maybeck made for Christine of the Daisy Dell area, his plans for the stage, and even for a residential studio he planned to build for her to live in.

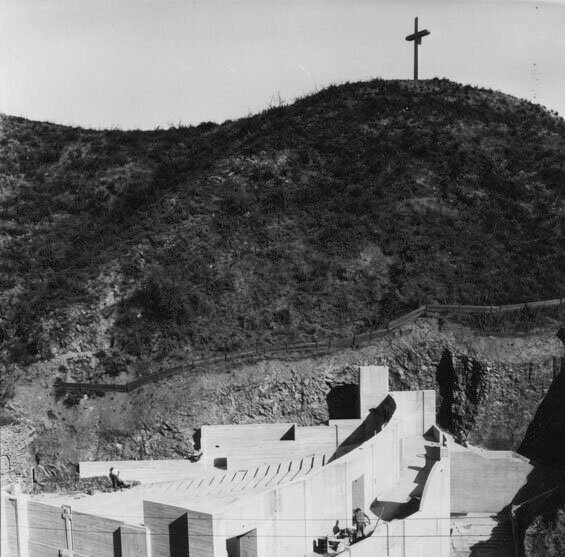

1923: The (Hollywood) Cross is Erected

A year after Christine Wetherill Stevenson’s death in 1922, a 40-foot wooden cross was erected in her honor on a hilltop above the Pilgrimage Theatre. It was illuminated with 1800 incandescent light bulbs during summer evening performances of the Pilgrimage Play below and during Easter sunrise services at the Hollywood Bowl across Cahuenga Blvd.

The Pilgrimage Theatre Association donated the cross and the land beneath it to Los Angeles County in 1941. The original wooden cross was destroyed by a brush fire in 1965, and the county replaced it with a steel and plexiglass cross. In the late 1970s, the ACLU worked to prevent public money from being used to maintain the cross, and since then, the cross has undergone several restorations at the hands of various religious organizations.

A cross still stands in that location today, now know as the Hollywood Pilgrimage Memorial Monument, and is one of Hollywood’s Historic-Cultural Monuments, designated by the city’s Cultural Heritage Commission.

1929: Fire Destroys Theatre

Amidst the stock market crash of 1929 that began the Great Depression, “a brush fire swept through the hills of Hollywood.” At first it was just another brush fire, one of the scores which sweep the tinder-dry hills every year. But directly in the path of the flames stood the wooden Pilgrimage Play Theatre, which even then had become an institution in Los Angeles and had been given world-wide acclaim. Firemen fought the brush fire to no avail. The Pilgrimage Theatre was destroyed. “To say this was a great blow to Los Angeles would be putting it mildly.” So declared the local Nuestro Pueblo newspaper.

1931: New Theatre Reopens

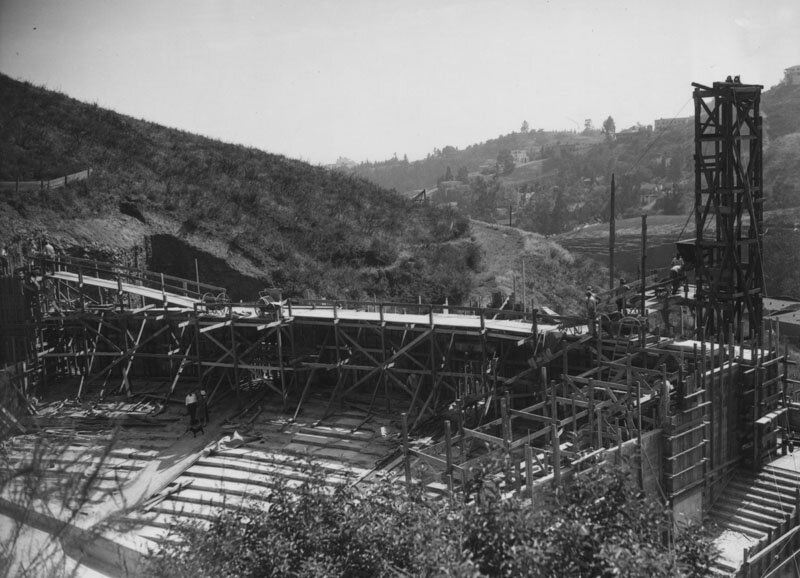

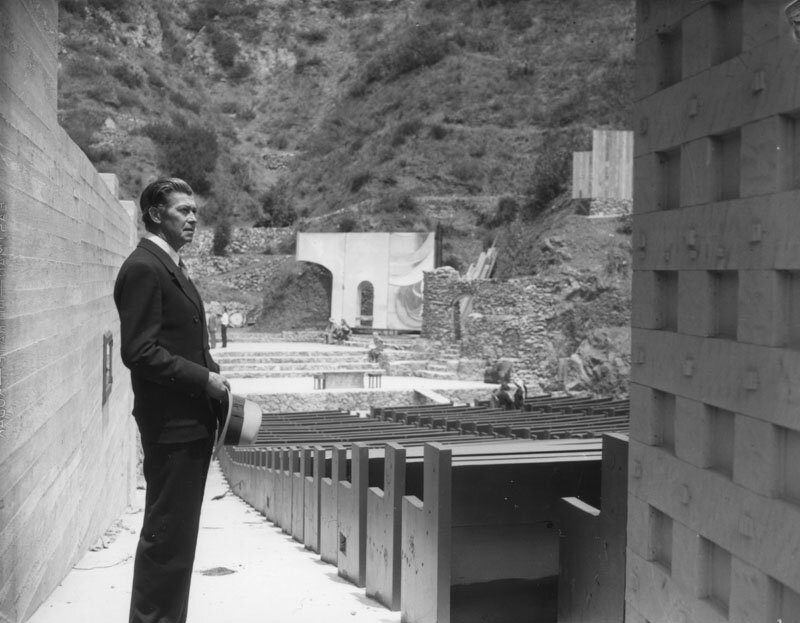

A new theatre was built on the same site, this time using the latest technology in poured concrete with architecture and landscaping meant to evoke the ancient city of Jerusalem. The architect of the amphitheatre, William Lee Woollett, had arrived in California shortly after the great 1906 San Francisco earthquake, with ideas there would be plenty of work for him to rebuild. Mrs. Clara Burdette & Mrs. Chauncey Clarke turned the first shovels on the new ground.

“A number of civic leaders sensing the great loss of the institution which for 10 years had meant so much to the community, set about re-building, in mortar and stone, a lasting edifice and on July 7th it was completed and given over to the Pilgrimage Play association. On the night of the 10th of July the theatre was dedicated and the play given before a large and distinguished audience. Though the building and surroundings take on the atmosphere of ancient Holy Land, the interior of the theatre is modern in every respect. The lighting which is achieved by means of huge flood lights, is wonderful in its effects. The lights and shadows across the hillside which forms a backdrop for the stage and where the cross stands, are beautifully real. The sunrise and sunsets and the glowing colored lights of the transfiguration and the ascension help to make the play a living event.”

Four Decades of The Pilgrimage Play Through a Changing World

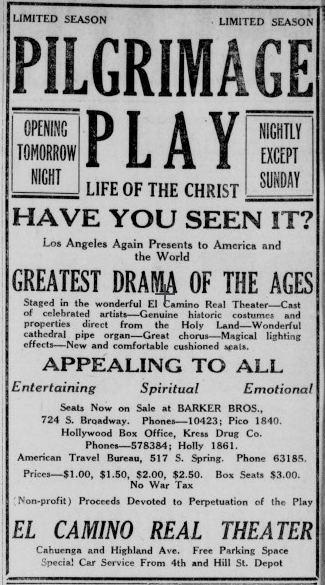

1920: The Pilgrimage Play Opens

“All day long, men with pickaxes and carpenters and mechanics labor in the El Camino Real Canyon, some in the natural amphitheatre in its valley, some crawling like flies on the steep heights 500 feet above them. Then at 4pm, those seeming laborers begin the acting of a play...The lines of the play teem with the noble language of the Bible and the actors, though they are dressed like laborers and many of them have just laid down their pick axes, enter into their parts as if inspired by a spirit of religious fervor. [A few days before opening], a reporter asked, “And what is the National Pilgrimage Play? I thought I was a pretty good Angeleno, but I never heard of it before.” “That’s one of the odd things about it,” answered John the Baptist, “New York knows more about it than Los Angeles does and has subscribed $10,000 for this play, which is to be made an annual event in Los Angeles and to which people from all America will make pilgrimages. It is not a money making project nor a publicity seeking project. It is simply an effort to establish in Los Angeles a play greater than the Passion Play at Oberammergau [running since 1634].”

1922: The Drama Attracting Many to the West

Within just a few summers, the Pilgrimage Play is attracting attention from across the country. The two-hour play features 150 men, women, and children, with 84 speaking parts as well as live horses and donkeys.

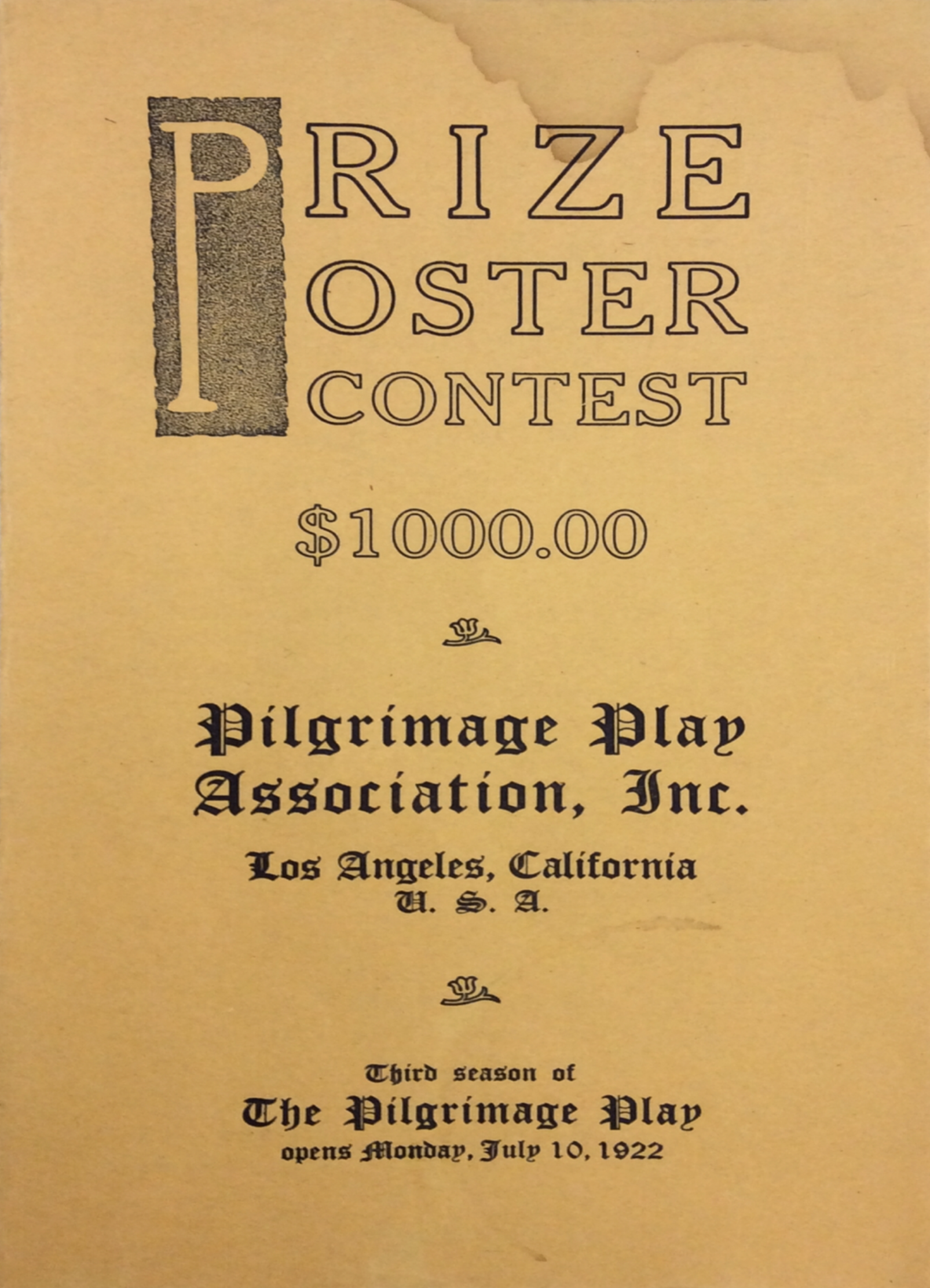

Graphic Design of Pilgrimage Play Promotional Materials

In 1922, the Pilgrimage Play Association begins offering to the artist who designs the best advertising poster for the play a $1,000 cash award, a nationally touring art show, and a press announcement to all of the leading newspapers and important art periodicals of the world. “It is to be hoped that a symbol of the Light of Life rather than the well-known figure of Jesus of Nazareth will be portrayed...Preferences will be given to more symbolic treatments,” described the judging committee. Though it’s unknown who the winner was or how long the contest endured, souvenir programs and flyers advertising the play would continue to show adventurous design choices for decades to come.

A collection of Pilgrimage Play souvenir programs 1924-1964:

1922: John Anson Ford First Tied to the Theatre

In 1920, John Anson Ford arrived in Los Angeles and began writing for local Hollywood community newspaper Holly Leaves, which often featured reviews or announcements about the Pilgrimage Play. From 1934-1958, Ford oversaw the Pilgrimage Play as Third District Supervisor and initiated major improvements to the theatre over the years. His son, John Arnold Ford, would go on to direct the Pilgrimage Play from 1955 onward, and his granddaughter Patti Ford Lavernoich appeared in the play as a baby. In 1976, when he was 92 years old and still contributing to city life, the theatre would be renamed the John Anson Ford Amphitheatre in his honor.

1928: Pacific Electric Streetcar Service to the Bowl

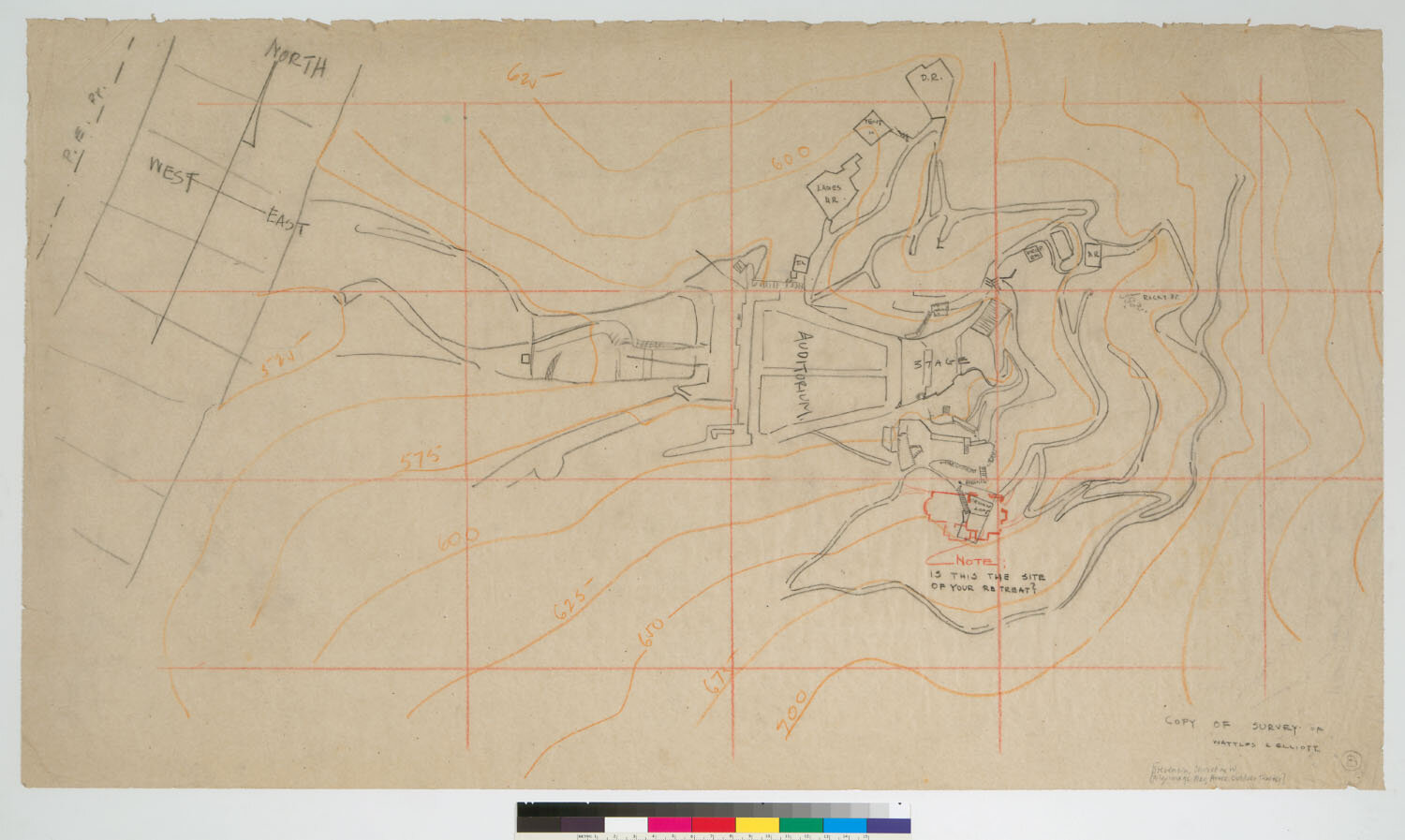

For the ninth-annual summer Pilgrimage Play run, attendees were encouraged to use the special Pacific Electric streetcar service directly to the Bowl in order to avoid the traffic that would eventually necessitate the Hollywood Freeway expansion. In the photos below, notice the new housing development plan on the left (Pilgrimage Theatre at center) and on the right, a Pilgrimage Plays banner in the hills above the streetcar.

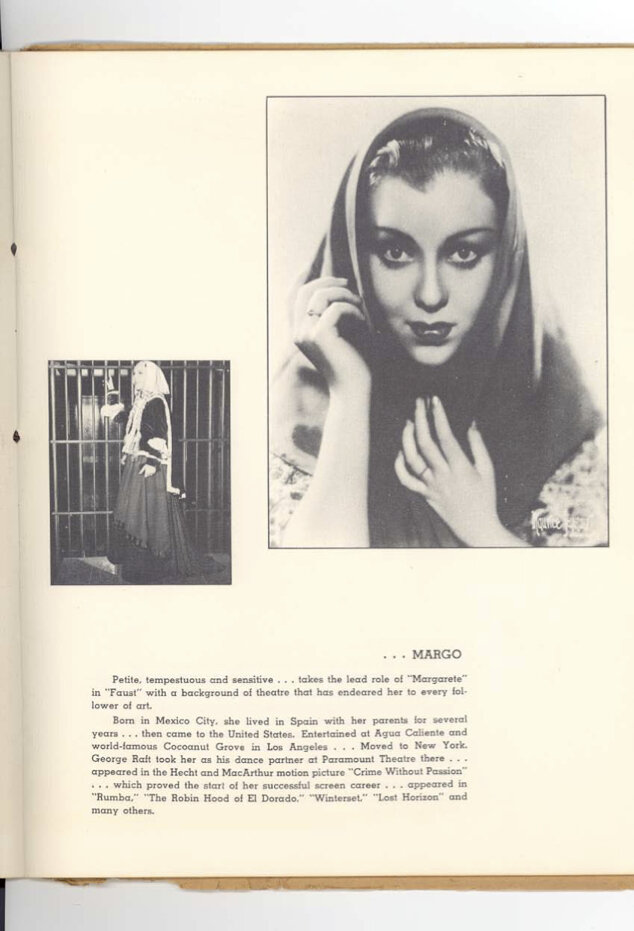

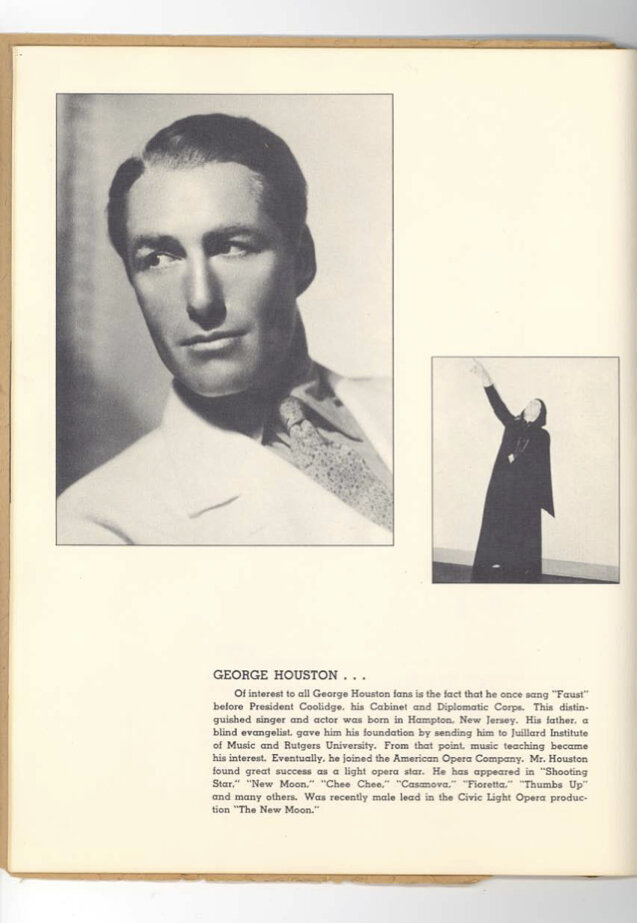

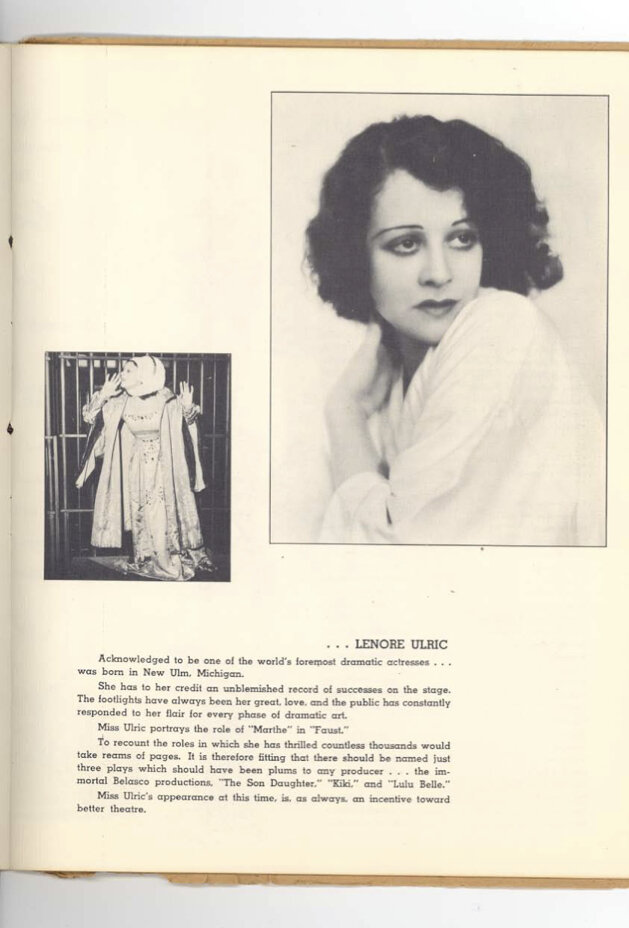

1938: Faust Has Fans Lining the Roadside to See Film Stars

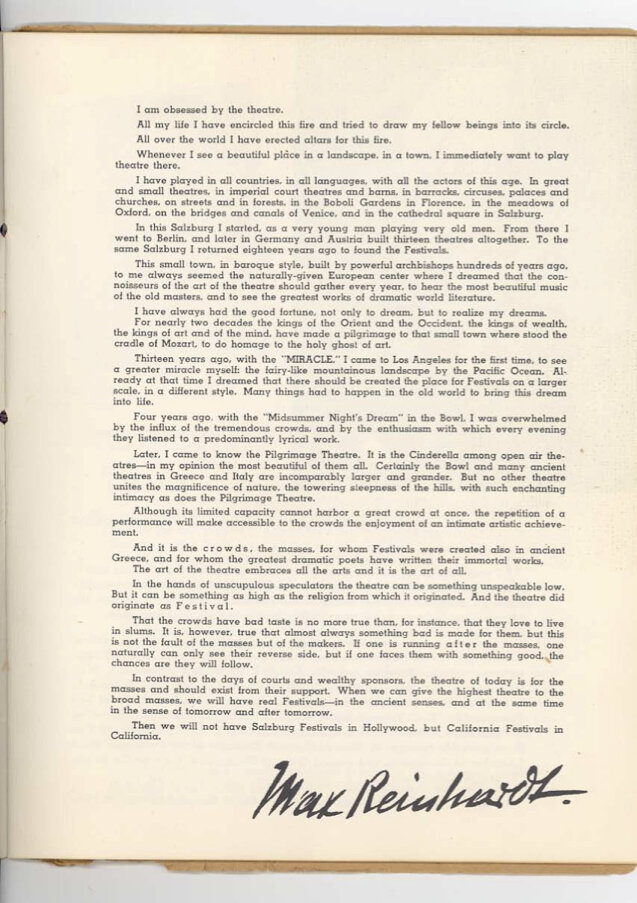

Prominent silver screen director Max Reinhardt oversaw the first major production at the Pilgrimage “Little Bowl” Theatre other than the annual Pilgrimage Play.

“Never at any time have we had such a setting for the Faust legend as the Pilgrimage Theater. It is this wonderful background of the hills of Hollywood that will make the new and more splendid Faust possible...The public, Reinhard feels, is the key to the entire situation...The spirit that the audience brings to a play is all important.”

“A star studded audience was on hand last night for the spectacular premiere presentation of Goethe’s Faust under the personal direction of the world-famous impresario Max Reinhardt at the Pilgrimage Outdoor Theater in Hollywood. Perfect weather greeted the 1700 spectators as the curtain went up on this elaborately presented play made possible through the California Festival Association...Long before famous film people began to arrive, motion picture fans gathered in the long runway to the entrance of the amphitheatre virtually blocking the passage to obtain signatures in their autograph books. It was truly like a Hollywood film premiere. Women were beautifully gowned and their escorts were dressed in the traditional evening attire. Those spotted in the audience include Jack Benny, Joan Crawford, Jack Warner, Bette Davis, and Lucille Ball.”

“The Pilgrimage Theatre is the Cinderella among open air theatres—in my opinion the most beautiful of them all. No other theatre united the magnificence of nature, the towering steepness of the hills, with such enchanting intimacy as does the Pilgrimage Theatre.”

Faust premiered at the tail end of the Great Depression. Notably, the two advertisers promoted in this Faust program are for furs and pianos.

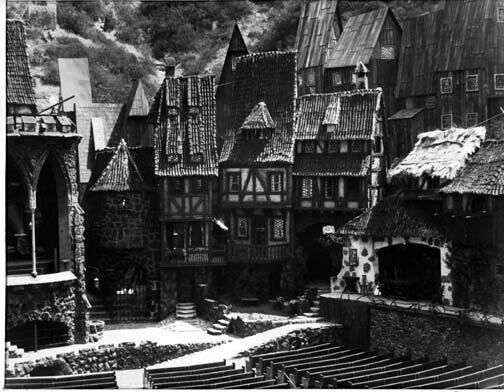

“The setting devised under Reinhardt’s direction is bound to captivate as soon as it is viewed, and that thrill awaits each one who enters the portals of the theater and takes in the remarkable perspective. A complete town of the Middle Ages with church, prison, tavern, street, and byway filled with quiet radiance, appears before the eye, surmounted on the heights by still other palaces of the imagination. That setting is the vital and living thing in Faust, a veritable masterpiece of architecture.”

California not-so-casual: Fritz Lang, director of the silent film classic Metropolis, is accompanied by his monocle and actress Miriam Hopkins on opening night, August 23, 1938. (Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library, Herald Examiner Collection)

In preparation for the Faust production, a major remodel of the theatre occurred, including widening the proscenium from 30 to 98 feet and adding side stages. The stunning completed set—the stonework and the familiar hillside backdrop were the only clues that it’s still the Pilgrimage. During this same time period, Los Angeles was second only to New York City for the number of personnel employed by the Federal Theatre Project, a New Deal fund sponsored by the Works Progress Administration. While FTP workers rebuilt parts of the Hollywood Bowl next door, no work is known to have taken place at the Pilgrimage Play Theatre.

Silver Screen Actors Get Their Start (or Their End) in the Pilgrimage Play

Nelson Leigh was a prolific motion picture star appearing in more than 130 films. He portrayed Jesus Christ in the Pilgrimage Play from 1936-1951, becoming an actor who has portrayed Christ and the Apostle Paul more than any other in history. His father passed away at the Pilgrimage Play Theatre, on his way hiking up the Hollywood hillside to his son’s dressing room, called “Heaven” because it was so far above the stage.

Fay Wray came on the Hollywood scene at age 15, appearing in silent pictures by day and in the Pilgrimage Play at night, all while studying at Hollywood High School. She appeared in the Pilgrimage Play during the early 1920s but ultimately became best known for starring in the 1933 King Kong.

William Faversham was one of the highest paid stage actors at the turn of the century earning upward of $5 million annually. By 1926, his fortunes had turned and he brought suit against the Pilgrimage Play Association after they offered him the role of Christ, shot publicity photos, and then fired him two weeks into the production for supposedly forgetting his lines for the Lord’s Prayer. By 1927, he filed for bankruptcy and never regained his former glory.

Robert Vaughn made his stage debut as Judas in the 1955 production of the Pilgrimage Play and became best known for his role as the suave spy Napoleon Solo in the 1960s TV series The Man from U.N.C.L.E. In his autobiography, Vaughn recalled, “I was paid a handsome five hundred dollars per week – not quite on par with the cool grand earned by the actor playing Christ, but better than the thirty pieces of silver received by the Biblical original.”

1941: County of Los Angeles Acquires the Property

When Christine Wetherill Stevenson passed away, her parents made a gift of the property to the Pilgrimage Play Association in August 1924 with a ten-year lease and a covenant that the play be produced each season, to be maintained on a nonprofit basis. Los Angeles Times owner Harry Chandler was an early friend and supporter of Christine’s and eventually acquired the property and the performance rights to the play on behalf of the Pilgrimage Play Association.

On October 17, 1941, the Pilgrimage Play Association, under the leadership of George L. Eastman, deeded the property to the County of Los Angeles, subject to a 99-year lease to the Hollywood Bowl Association on terms similar to the Hollywood Bowl lease.

1941-1943: Theatre Closes for Wartime

During the war, dressing room sections of the Pilgrimage Theatre were converted into dormitories where hundreds of servicemen slept during visits to Hollywood. The annual Pilgrimage Play went on hiatus for three summers, but was back in preparation for it’s 19th annual run by the time John Anson Ford sent this letter. September 2, 1945, the final day of World War II would fall on closing night of that season’s Pilgrimage Play run. For several months afterward, the Pilgrimage Theatre would continue to host servicemen returning home in the dressing room dormitories.

1949: The Pilgrimage Play Movie Premieres

In May 1949, The Hollywood Reporter announced that Ralph Ravenscroft had completed a deal with the Hollywood Bowl Association to film a 35mm color version of the stage play. Most of the cast of the stage play, including Nelson Leigh, Stephen Chase, Leonard Penn, Richard Hale and Fiona O'Shiel, recreated their roles in the film version. The movie was shot on-site at the Pilgrimage Play Theatre and a nearby soundstage. Lead actor Nelson Leigh portrayed Christ in the film and in the live production annually going back to his days as a senior at USC in 1925. Although the picture was shot in 16mm and was intended primarily for showings in churches, The Hollywood Reporter review announced that 35mm prints were being made for screenings in "art theatres in this country and possibly in England." One-third of the film's profits were to go to the Pilgrimage Play Foundation, which funded the play's annual production, according to the May 1949 Hollywood Reporter item. The Copyright Catalog indicates that a "Catholic version" of this "Protestant version" was released as Upon This Rock.

1952-1954: Theatre Closes for Hollywood Freeway Expansion

In the first few years of the theatre’s existence, the venue was known as the Camino Real Theatre, named after the 18th century Camino Real del Rey linking the missions of Alta California together. By 1922, 25 streetcars and 17,000 cars were crossing through the Cahuenga Pass daily on the old wagon road and traffic was already called “intolerable.” Car traffic had surpassed 50,000 per day by 1939 when the Cahuenga Pass Parkway (State Highway #2) was built. In 1952, the Pilgrimage Theatre closed for two years to allow for the parkway to be expanded. In 1954, the Hollywood Freeway expansion opened and only a year later, the Freeway was being used by an average of 183,000 vehicles a day, almost double the capacity it was designed to carry.

1955: John Arnold Ford Takes Over

Opera singer John Arnold Ford would revive and reopen the theatre, producing the Pilgrimage Play from 1955-1961. He was the son of John Anson Ford, the Los Angeles County supervisor from 1934-1958 for whom the venue was renamed after its maintenance was taken over by the county Parks and Recreation Department in 1961. John Arnold Ford first developed an interest in music as a high school student and soon began singing professionally with opera companies across the West. He served in World War II, performing alongside Mario Lanza in the Special Services division. After the war, he performed as a soloist at the Hollywood Bowl, and founded a popular opera-in-schools program, all the while directing the Pilgrimage Play for its final seven seasons.

1961: Lawsuit Prohibits Local Government from Funding the Play

In an opinion involving the separation of church and state on April 10, 1961, Attorney General Stanley Mosk ruled that the County of Los Angeles could not contribute tax funds to the Pilgrimage Play, which allegedly promoted a particular religion, despite the contention that the state support should escape constitutional scrutiny because of the play's widespread fame and benefit as a tourist attraction. At the time, the County was contributing $20,000 per year to fund the production. Mosk would go on to become the longest serving justice on the California Supreme Court and this case would help set historic precedent around the separation of church and state.

1964: Final Pilgrimage Play Production

After 32 seasons, a final performance run of the Pilgrimage Play is produced by the Hollywood Bowl Theatre Association with enough private money to pay for a cast of about 100 and fill the 1,312-seat theater. Over nearly five decades, the production drew more than 1 million Southland residents to witness the spectacle. Being Hollywood, many celebrities found their way to the Pilgrimage Play over the years.